SCHLEICHER/LANGE PARIS

CHRIS CORNISH: SAMPLE AND HOLD

11 September, 2010 - 9 October, 2010

-

Chris Cornish’s work probes the boundaries and negotiates the exchanges between real and virtual. It also has its place in the tradition of pictorial image. In this way, the work places in the same trajectory the perspective machine, whose grid can be seen as a prototype of the digital draughtboard, and new image technology. But while Chris Cornish’s pieces are permeated by pictorial representation, monochrome and abstraction, they also express an awareness of the medium that harks back to the 1960s.

Situated on the border between the real and virtual worlds, between the palpable universe and the vast spectrum of its translations, the work of this British artist investigates and shows what happens between the “read” space and the image that emerges from it, or, in his own words, “what happens when geometry and mythology are pulled from one simulation to another”.

This is the meaning behind the title of the artist’s first solo exhibition at the gallery, Sample and Hold (the circuit that changes analogue signals to digital signals), the duality specific to all sources of information caught between two languages, two readings, two interpretations. But rather than restricting his practice to such translations, Chris Cornish often draws on powerful symbolic contexts and unravels their structures.

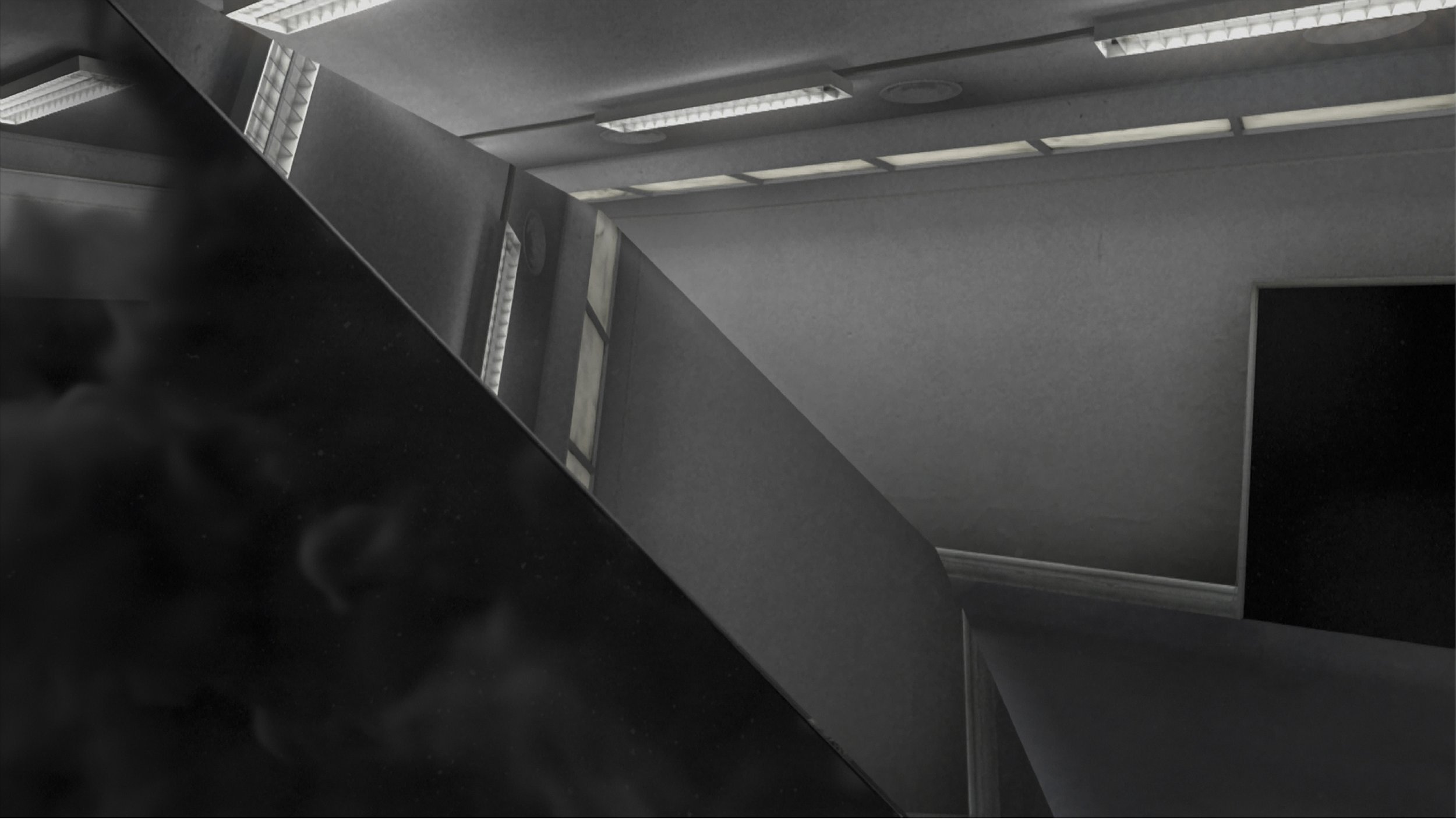

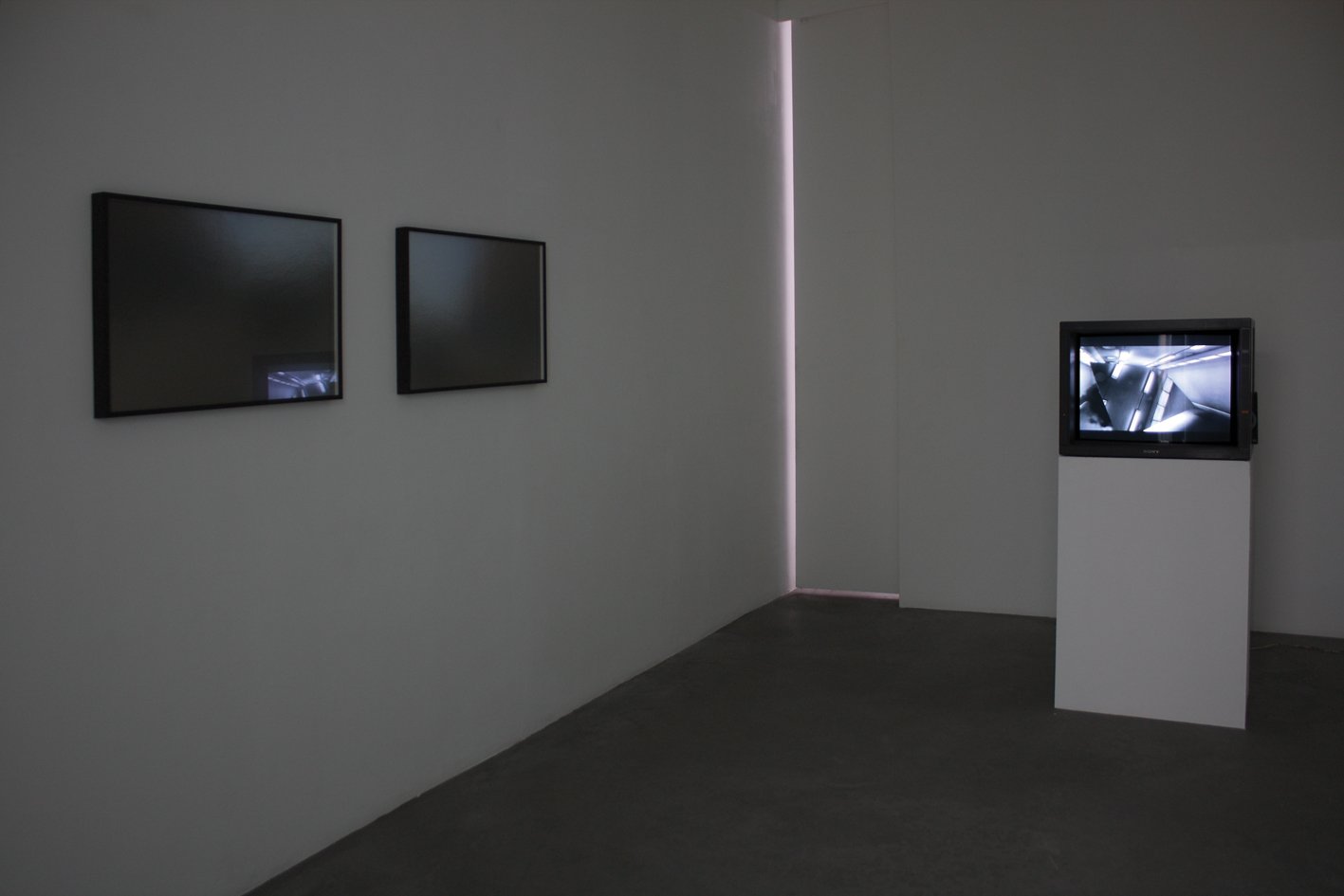

The first piece the spectator encounters on entering the exhibition is The Zone (2008-2010). The title refers to the ‘Zone’ in Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 film, Stalker. The piece is, however, much more than a mere reference to the film; it is a digital dissection of the film via a method of image analysis used for special effects and the insertion of virtual elements into film sequences. This technique pinpoints the points of interest in an image sequence by marking their movement over time, thereby enabling the space to be faithfully recreated without reproducing its exact image. The sculpture The Zone represents rather the reading of this imaginary place, which supposedly has the potential to fulfil a person’s innermost desires. Just like the Zone, the eponymous sculpture carries a meaning which its appearance does not lay bare but which it incarnates symbolically: the superimposition of the real and the ideal.

This relationship arises again in a second sculpture, also called Sample and Hold (2010), which stands opposite The Zone, in the same room. This readymade stands at the heart of the exhibition, but remains entirely enigmatic. This sphere is a functional yet curious-looking object. One side polished mirror, the other flat and grey, it is reminiscent of diabolical machines, a sort of disembodied character with panoptic vision, or simply a highly modern crystal ball. It records the environmental properties of any given space and is used to to match computer-made objects to a real environment. Thus, like Descartes’ pineal gland, which communicates between body and mind, or the divine eye that sees and knows everything, the sphere is a gateway into another dimension that bears the vestiges of our own.

In the same room, tying in with the works described above, is Environment (2010), a series of photographs made by 3D scanning the walls of the gallery. The images are positioned at the place where they were taken. The piece draws on the literal logic of certain conceptual works of the 1960s, which tautologically slipped reality into the possible translations of a given thing (Joseph Kosuth’s definitions provide the main example of this). Here, however, Environment draws attention to the duplication of the image and its capacity to provide a trace of reality, while at the same time lending it a virtual aura. Looking closely, it is easy to detect the trick of the light, which, as in Renaissance painting, guides the viewer’s gaze and dramatises by artificial means that build up an illusion of both reality and divine omniscience, prefiguring cinema.

Flat Earth (2010) is to some extent a response to Environment (in the second room). The artist has used the technique of normal mapping so that the two images constituting Flat Earth reproduce the sphere of Sample and Hold. Normal mapping records the impression of a 3D surface by creating an RGB image that corresponds to the X, Y, and Z coordinates of the surface direction of an object. The extracted colour field enables 3D data to be spatialised in a 2D plane, as Chris Cornish explains: “This means 3D space information is contained within every pixel of an image,” or simply that this coloured chart is the volume of a sphere. Whereas the wall in the previous room sees the superimposition of the object and its image, here we are confronted with a projection containing an entire volume, as the planisphere flattens and reveals the terrestrial globe. The originality of these uses of synthesis images lies in introducing them into the traditional language of painting - normal mapping can be an extreme form of chiaroscuro -, leading to pertinent observations but also “optical aberrations”. The adventure and the resolution (2010), the film in the last room, demonstrates this. The film documents a computer generated aberration; the creation of an illusion that must reveal its mechanics to be sustained. Situated in a computer representation of a real environment, the camera circles, producing a film loop that becomes a contemporary Zoetrope; an apparatus of transformation. Sample and Hold is a foray into fictional spaces and their particular mechanisms, their ability to induce entire worlds, as well as the possible translation of three-dimensionality which makes reality into an experience that is infinitely translatable into a broad spectrum of codes, surfaces and textures. This strange malleability forges contemporary mythology, which reveals as much about how we relate our stories as the stories themselves.